That First CUDA Blog I Needed :Part 2

In the previous part of this blog, Part 1: Foundations of GPU Thinking, we laid the groundwork — understanding the GPU mindset, setting up CUDA, and writing our very first kernel. That was the spark. Now, in Part 2, we dive deeper into how CUDA organizes and runs thousands of threads, and how data flows between the CPU and GPU.

Part 2: Building Blocks of Parallelism

4. Thread Organization in CUDA

5. Managing Data: From CPU to GPU and Back

All the code related to this blog series, accompanying each step of your CUDA learning journey, can be found on GitHub at: https://github.com/sanket-pixel/blog_code/tree/main/8_that_first_cuda_blog.

4. Thread Organization in CUDA

In the previous section, we briefly saw this line , gpu_hello_world<<<1,8>>>();. We used it without explaining what <<<1,8>>> means. To truly understand CUDA programming, it’s important to unpack this syntax. This leads us to understanding how threads are organized in CUDA.

4.1 Heirarchy in CUDA

When you launch a CUDA kernel, you typically launch many threads, not just one. These threads are organized in a hierarchical structure as shown in the figure below.

Each kernel launch, creates one Grid, which contains many Blocks, which in turn contains many Threads.

To understand how the threads, blocks and grids are organized, let us use the analogy of a building with 3 floors, and with 4 apartments on each floor. Thus we have 12 apartments in total.

Each thread is like an apartment (flat) on the floor.

Each block is like a floor in the building.

The grid is the entire building.

This maps to <<<3, 4>>> in CUDA, which means launching 3 blocks, each containing 4 threads — totaling 12 threads. The two parameters inside the kernel launch syntax <<<gridDim, blockDim>>> represent the number of blocks in the grid (gridDim) and the number of threads in each block(blockDim).

4.2 Finding global index of a thread

In CUDA, thousands of threads may run in parallel, and each thread typically processes a different portion of data—like one element in an array. To do this correctly, each thread must know exactly which piece of data it’s responsible for. That’s where the global thread index comes in: it gives every thread a unique ID across the entire grid so it can access the correct memory location.

Extending our analogy as shown above, if every flat needs a unique global ID across the entire building, we do this: I’m on floor floorIdx, in flat flatIdx. Multiply the floor number by the number of flats per floor (floorDim) and add the flat index flatIdx.

int global_flat_id = floorIdx * floorDim + flatIdx;

For example :

Flat 2 on Floor 1: 1 * 4 + 2 = 6

Flat 3 on Floor 2: 2 * 4 + 3 = 11

In the figure above, GID refers to the global_flat_id . As shown on the left, every flat has a unique ID ranging from 0 to 11.

Along similar lines, to get the global thread index, we can use the blockIdx, blockDim and threadIdx. CUDA gives us built-in variables to retrieve this information:

blockIdx.x→ which block (floor) you’re in

threadIdx.x→ which thread (room) inside the block

blockDim.x→ how many threads per block (rooms per floor)

Using these, every thread can compute its global ID using:

int global_thread_id = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

This index lets the thread determine exactly which data element to work on.

Let’s look at a simple example where each thread doubles one element in an array:

__global__ void double_elements(int* arr) {

int idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

arr[idx] = arr[idx] * 2;

}

In this kernel, every thread calculates its global index and uses it to access the correct element in arr. Thanks to this indexing, all threads operate independently, and no two threads overwrite each other’s work.

4.3 A Hands-on Example: Squaring Numbers in Parallel

Let us now walk through a concrete example to reinforce what we’ve learned about thread organization in CUDA. This example not only demonstrates how threads are structured using blocks and grids but also highlights some important subtleties that apply to most CUDA kernels you will write.

We’ll square numbers from 0 to 9 in parallel. Each thread computes its global ID and prints the square of its assigned number.

#include <iostream>

#include <cuda_runtime.h>

#define THREADS_PER_BLOCK 4

#define DATA_SIZE 10

__global__ void print_square() {

unsigned int id = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (id < DATA_SIZE) {

printf("Thread %d: %d squared = %d\n", id, id, id * id);

}

}

int main() {

// compute how many blocks we need

int blocks = (DATA_SIZE + THREADS_PER_BLOCK - 1) / THREADS_PER_BLOCK;

print_square<<<blocks, THREADS_PER_BLOCK>>>();

cudaDeviceSynchronize();

}

How to run it:

- Navigate to the directory:

cd 8_that_first_cuda_blog/2_squared_numbers - Compile the program:

nvcc squared_numbers.cu -o squared_numbers - Run the executable:

./squared_numbers - You’ll see output like:

Thread 0: 0 squared = 0 Thread 1: 1 squared = 1 Thread 2: 2 squared = 4 // and so on...

This diagram below visually explains how CUDA computes each thread’s global ID using blockIdx.x, threadIdx.x, and blockDim.x. It also shows which threads execute the computation based on the condition if (id < DATA_SIZE).

Let’s break down the key ideas:

- We define two constants at the top:

-

THREADS_PER_BLOCK = 4→ Each block contains 4 threads. -

DATA_SIZE = 10→ We want to square numbers from 0 to 9.

-

- In

main(), we compute how many blocks we need. As shown in the figure above,int blocks =3:int blocks = (DATA_SIZE + THREADS_PER_BLOCK - 1) / THREADS_PER_BLOCK; - We launch the kernel:

print_square<<<blocks, THREADS_PER_BLOCK>>>(); - Inside the kernel, each thread calculates its global ID:

unsigned int id = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; - The check

if (id < DATA_SIZE)ensures that no thread attempts to process an index beyond the data size — an essential safeguard when the total number of threads exceeds the amount of data.

4.4 Thread and Block IDs in 2D and 3D

So far, we’ve been using variables like threadIdx.x, blockIdx.x, and blockDim.x in our CUDA kernels — but we haven’t really explored what the .x means, or what happens when we go beyond 1D.

Understanding how threads and blocks are structured in multiple dimensions (2D and 3D) is essential because many real-world problems are naturally multi-dimensional — like image processing (2D pixels), volumetric data (3D grids), or matrix operations. CUDA’s thread hierarchy lets us mirror this structure directly, so we can write cleaner, more intuitive code.

In CUDA, both threads and blocks can be organized in 1D, 2D, or 3D layouts. That means:

- Each block can have threads arranged like a line (1D), a grid (2D), or a cube (3D).

- Similarly, the grid of blocks itself can follow any of these layouts.

Each thread and block has 3 coordinate components:

-

threadIdx.x,threadIdx.y,threadIdx.ztell you the thread’s position within its block. -

blockIdx.x,blockIdx.y,blockIdx.ztell you the block’s position within the grid -

blockDim.x,blockDim.y,blockDim.ztell you how many threads are there per block in each direction

This gives every thread a unique multi-dimensional ID — but to index into flat memory like an array, we typically compute a flattened 1D global index from these coordinates.

2D grid and blocks

Let’s say each block is a 2D grid of threads and the entire grid has a 2D arrangement of blocks. Then, we compute a flattened global thread ID like this:

int x = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

int y = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y;

You now have coordinates (x, y) representing the thread’s unique position in the global 2D grid. If you want to flatten this into a 1D index (e.g. for array access), you can do:

int idx = y * total_width + x; // where total_width is the width of the full grid

3D grid and blocks

In case the grid has blocks in 3D, and the blocks have threads in 3D,

int x = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

int y = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y;

int z = blockIdx.z * blockDim.z + threadIdx.z;

And to get a linear index:

int idx = z * (height * width) + y * width + x;

These computations let each thread know exactly what data to work on, even in multi-dimensional problems. CUDA doesn’t care if you use 1D, 2D, or 3D — it just provides the structure so you can map the problem domain naturally and write code that’s easier to reason about.

TL;DR: Think of .x, .y, and .z as the coordinates in a virtual 3D thread universe. You use them to uniquely identify and assign work to each thread, especially in problems where your data naturally lives in 2D or 3D.

Let’s Understand This with a Concrete 2D Example

#include <iostream>

#include <cuda_runtime.h>

#define WIDTH 10 // width of simulated 2D data (columns)

#define HEIGHT 5 // height of simulated 2D data (rows)

#define THREADS_X 4 // threads per block in X

#define THREADS_Y 2 // threads per block in Y

__global__ void print_2d_coordinates() {

// Get global 2D index

int global_x = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

int global_y = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y;

// Compute linear ID (row-major order)

int global_id = global_y * WIDTH + global_x;

if (global_x < WIDTH && global_y < HEIGHT) {

printf("Block (%d,%d) Thread (%d,%d) → Global ID: %2d → Pixel (%d,%d)\n",

blockIdx.y, blockIdx.x, threadIdx.y, threadIdx.x, global_id, global_y, global_x);

}

}

int main() {

dim3 threads_per_block(THREADS_X, THREADS_Y);

int blocks_x = (WIDTH + THREADS_X - 1) / THREADS_X;

int blocks_y = (HEIGHT + THREADS_Y - 1) / THREADS_Y;

dim3 num_blocks(blocks_x, blocks_y);

print_2d_coordinates<<<num_blocks, threads_per_block>>>();

cudaDeviceSynchronize();

}

To execute this program on your machine, follow the following steps :

- Navigate to the directory 8_that_first_cuda_blog/3_print_2d_coordinates

cd 8_that_first_cuda_blog/3_print_2d_coordinates - Compile the program using the following command

nvcc print_2d_coordinates.cu -o print_2d_coordinates - This will create an executable

print_2d_coordinatesin this directory. Execute it using./print_2d_coordinates - The output will start with something like :

Block (2,2) Thread (0,0) → Global ID: 48 → Pixel (4,8) Block (2,2) Thread (0,1) → Global ID: 49 → Pixel (4,9) Block (2,1) Thread (0,0) → Global ID: 44 → Pixel (4,4) Block (2,1) Thread (0,1) → Global ID: 45 → Pixel (4,5) Block (2,1) Thread (0,2) → Global ID: 46 → Pixel (4,6) Block (2,1) Thread (0,3) → Global ID: 47 → Pixel (4,7) // and so on..

In this code :

- We’re simulating a 2D image of size

10 x 5(10 columns × 5 rows). - Each block is configured to launch 4 x 2 threads. ( blockDim.x=4, blockDim.y=2)\

- Based on the data dimensions and thread layout, we calculate how many blocks we need in X and Y directions:

int blocks_x = (WIDTH + THREADS_X - 1) / THREADS_X; int blocks_y = (HEIGHT + THREADS_Y - 1) / THREADS_Y; - Inside the kernel, each thread computes:

- Its global X and Y position using its thread and block indices

- A linear global ID, assuming row-major layout

// Get global 2D index int global_x = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; int global_y = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y; // Compute linear ID (row-major order) int global_id = global_y * WIDTH + global_x; -

The

ifcondition:if (global_x < WIDTH && global_y < HEIGHT)ensures that only threads within bounds print output. Without this, some threads (especially in the last block row/column) might run out-of-bounds and access invalid pixels.

- In the earlier 1D example, we used plain integers like

<<<blocks, threads>>>. In this 2D case, we usedim3to pass 2D configurations — a CUDA struct that lets us naturally map threads to 1D, 2D, or 3D data layouts.

As shown above, for an image of 10x5 with and blockDim of (4,2), the gridDim is (3,3). To compute the global thread ID of the thread marked in red :

blockIdx = (1, 0) → 2nd block in X, 1st in Y ( highlited in yellow )

threadIdx = (1, 2) → row 1, column 2 within the block ( highlited in red)

global_x = blockIdx.x × blockDim.x + threadIdx.x

= 1 x 4 + 2 = 6

global_y = blockIdx.y × blockDim.y + threadIdx.y

= 0 x 2 + 1 = 1

global_id = global_y x WIDTH + global_x

= 1 x 10 + 6 = 16

That wraps up our section on thread organization — we now understand how threads and blocks are structured and how they map to data. Whether 1D or 2D, it’s all about aligning the thread layout to your problem.

Next, we’ll explore how memory works in CUDA — including how to allocate memory on the GPU and transfer data between the CPU and GPU.

5. Managing Data: From CPU to GPU and Back

In this section, we’ll understand how data moves between the CPU and GPU, and why explicit memory management is crucial in CUDA programming.

Here, we only see the essentials, but you can check out my previous blog post Down the CUDA Memory Lane for a deep dive into CUDA Memory.

Before diving deeper, it’s important to understand a key idea —the CPU (host) and GPU (device) have separate memory spaces. They do not share memory by default and cannot directly access each other’s data. If you want the GPU to work on data from the CPU (or send results back), you must explicitly transfer that data between the two.

There are a few subtle but essential things to keep in mind:

- Simply defining an array on the CPU doesn’t make it visible to the GPU.

- The GPU cannot allocate or manage host memory directly.

- Data must be copied from host to device before the kernel runs, and back afterward if needed.

- Memory transfers are relatively expensive compared to computation, so minimizing them is often important for performance.

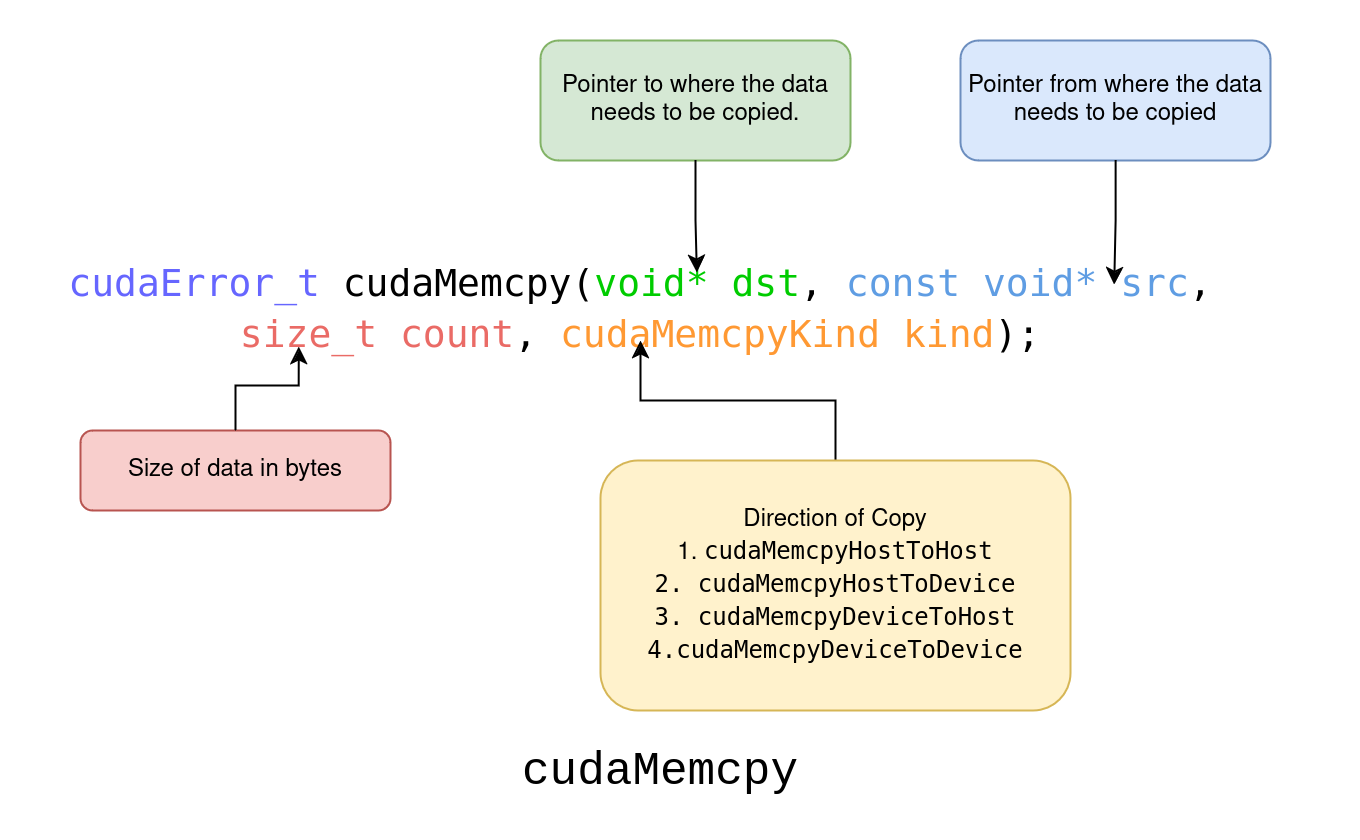

In this section, we’ll briefly summarize how to allocate memory using cudaMalloc and copy data with cudaMemcpy, just enough to get us started with real examples.

As always, lets first directly look at a working example and then understand these memory management thought that.

#include <iostream>

#include <cuda_runtime.h>

int main() {

// Step 1: Allocate Memory on the CPU for an Integer Array of Size 10

size_t size = 10 * sizeof(int);

// Allocate memory on the CPU (host)

int *h_array = (int*) malloc(size);

if (h_array == nullptr) {

std::cerr << "Failed to allocate CPU memory" << std::endl;

return EXIT_FAILURE;

}

// Step 2: Allocate Memory on the GPU for an Integer Array of Size 10

int *d_array;

cudaError_t err = cudaMalloc((void**)&d_array, size);

if (err != cudaSuccess) {

std::cerr << "Failed to allocate GPU memory: " << cudaGetErrorString(err) << std::endl;

free(h_array); // Free CPU memory if GPU allocation fails

return EXIT_FAILURE;

}

// Step 3: Initialize the CPU Array with Squares of Integers from 1 to 10

for (int i = 0; i < 10; ++i) {

h_array[i] = (i + 1) * (i + 1); // Squares of integers from 1 to 10

}

// Step 4: Copy Data from the CPU to the GPU

err = cudaMemcpy(d_array, h_array, size, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);

if (err != cudaSuccess) {

std::cerr << "Failed to copy data from CPU to GPU: " << cudaGetErrorString(err) << std::endl;

cudaFree(d_array); // Free GPU memory if copy fails

free(h_array); // Free CPU memory

return EXIT_FAILURE;

}

// Step 5: Copy the Data Back from the GPU to the CPU

err = cudaMemcpy(h_array, d_array, size, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost);

if (err != cudaSuccess) {

std::cerr << "Failed to copy data from GPU to CPU: " << cudaGetErrorString(err) << std::endl;

cudaFree(d_array); // Free GPU memory if copy fails

free(h_array); // Free CPU memory

return EXIT_FAILURE;

}

// Step 6: Print Values to Verify It All Works

for (int i = 0; i < 10; ++i) {

std::cout << h_array[i] << " ";

}

std::cout << std::endl;

// Free the allocated memory

cudaFree(d_array);

free(h_array);

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

In this example, we prepare a list of 10 numbers on the CPU, send it to the GPU, bring it back, and check that everything transferred correctly. To achieve this, we perform the following operations : In this example, we will perform the following operations:

- Allocate memory on the CPU for an integer array of size 10

int *h_array = (int*) malloc(size);malloc, short for “memory allocation,” is a standard C/C++ function that reserves a block of memory on the CPU. - Allocate memory on the GPU for an integer array of size 10

cudaError_t err = cudaMalloc((void**)&d_array, size);cudaMallocis the CUDA equivalent ofmalloc, used to allocate memory on the GPU.Even though d_array is created in CPU code, it doesn’t store a regular number — it stores the address of memory that lives on the GPU. It’s like a note on the CPU that says, “Hey, the actual data is over there on the GPU.” The function takes a pointer to the pointer (&d_array) and the size in bytes.

SincecudaMallocexpects avoid**, we pass the address of the pointer (&d_array) so it can fill it with the location of the allocated GPU memory. Think of it like this: we’re giving CUDA a place to write down the GPU address, and after the call,d_arraywill hold the actual memory location on the GPU. It’s a bit of a tongue twister — passing the address of an address — but that’s how the pointer gets set correctly.

- Initialize the CPU array with squares of integers from 1 to 10

for (int i = 0; i < 10; ++i) { h_array[i] = (i + 1) * (i + 1); // Squares of integers from 1 to 10 } - Copy the data from the CPU to the GPU

err = cudaMemcpy(d_array, h_array, size, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice);cudaMemcpyis used to transfer data between the CPU and GPU. Here, we’re copying data from the CPU arrayh_arrayto the GPU arrayd_array. The last argument,cudaMemcpyHostToDevice, tells CUDA the direction of the copy. This step is crucial — the GPU can’t access CPU memory directly, so we have to send it over manually. - Copy the data back from the GPU to the CPU

err = cudaMemcpy(h_array, d_array, size, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost);This line copies the results from GPU memory (

d_array) back to CPU memory (h_array). The direction flagcudaMemcpyDeviceToHosttells CUDA we’re transferring data from the GPU to the CPU.

With this, we’ve covered the basics of how to manage memory between the CPU and GPU — a crucial foundation for any CUDA program.

This ends the Part 2: Building Blocks of Parallelism, where we explored the core building blocks of parallelism, how threads are organized into blocks and grids, and how data moves between CPU and GPU memory. These concepts are the backbone of writing scalable CUDA code.

In Part 3: A Real-World CUDA Project, we’ll put all this knowledge to use by building a practical example: converting a color image to grayscale on the GPU. Along the way, we’ll also discuss common pitfalls and wrap up your first CUDA learning journey.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: