That First CUDA Blog I Needed

Your code is powerful, but what if you could multiply that power by thousands? This blog is your invitation to unlock a completely new dimension of computing: the world of GPUs. We’ll bypass the overwhelming technical jargon and dense documentation, offering the clarity and right starting point you need to truly grasp parallel thinking. This is the plain-language guide I longed for when I began, explaining not just how to write CUDA, but the fundamental principles that make it tick. Whether you’re aiming for faster AI, robust system performance, or just curious about what lies beyond sequential code, welcome. Let’s embark on this journey to parallel mastery.

A new revolution is unfolding before our eyes: AI isn’t a distant dream anymore but it’s here, reshaping everything from art to healthcare. At the heart of this transformation lies the GPU, a powerhouse that can juggle thousands of tasks simultaneously and make ideas that once lived in science fiction become real. If CPUs are our trusty multi-tools, GPUs are the industrial engines that crank out massive workloads in parallel. And to talk to these engines, we use CUDA, a simple yet powerful language that lets us translate our ideas into blazing-fast GPU code.

When I first dove into CUDA, there wasn’t a single blog post that walked me through everything I needed: the mindset shift, the basic kernels, the data wrangling, and finally a real-world example. That’s exactly why I wrote “That First CUDA Blog I Needed.” I wanted something personal, something that says, “I’ve been there, I felt the confusion, and here’s a friendly guide to help you leap over those hurdles.”

This series is broken into three parts:

Part 1: Foundations of GPU Thinking

1. The Paradigm Shift from CPU to GPU World

2. Groundwork: What CUDA Assumes You Know

3. Your First CUDA Kernel: Hello World!

Part 2: Building Blocks of Parallelism

4. Thread Organization in CUDA

5. Managing Data: From CPU to GPU and Back

Part 3: A Real-World CUDA Project

6. Your First Real CUDA Example: Grayscale Conversion

7. Common Pitfalls When Getting Started

8. That’s a Wrap — Now You’re CUDA-Capable

By the end of this journey, I hope you’ll feel as excited (and a little humbled) as I did when my first GPU code ran without crashing. You won’t just have written some kernels—you’ll have joined a community of people who are building the future, one parallel thread at a time. Welcome, and let’s get started on what really matters.

All the code related to this blog series, accompanying each step of your CUDA learning journey, can be found on GitHub at: https://github.com/sanket-pixel/blog_code/tree/main/8_that_first_cuda_blog.

1. The paradigm shift from CPU to GPU World

Programming for the GPU isn’t just about speed — it’s about scale. A GPU isn’t a faster version of your CPU. It’s a completely different machine built with a different philosophy: do many small things all at once, not one big thing faster.

On the CPU, you’re the expert chef in the kitchen, handling every dish end-to-end with precision. On the GPU, you’re the head of a large team of cooks, each chopping, frying, or seasoning in parallel. The job gets done faster not because each cook is faster than you — but because you’re not doing it alone.

This mental shift is the first and most important leap. When we write CPU code, we think step by step: first do this, then that, then the next. But with GPUs, you have to learn to think like a parallelist: How can I break this task into a thousand identical pieces that can run simultaneously, without waiting on each other?

That’s the real challenge for most beginners — not the CUDA syntax, not the memory allocation APIs, but this fundamental change in mindset. The GPU model asks: “If I gave you 10,000 workers, each capable of doing the same thing — how would you structure the task?”

CUDA doesn’t want you to program the solution to your problem.

It wants you to program the solution to a small piece of your problem — and let the GPU handle the rest.

The good news? Once this clicks, everything else starts to make sense.

The bad news? You’ll never look at your CPU code the same way again.

Let’s say we want to multiply each number in an array by 2.

On the CPU, you would think sequentially as shown below :

for i from 0 to N-1:

output[i] = input[i] * 2

Here, you think like a single worker walking through the entire list, one element at a time.

While on the GPU you must think of processing in parallel as shown below :

function worker(i):

output[i] = input[i] * 2

launch N workers:

each runs worker(i) with its own i

Instead of one worker doing the whole loop, you write code for just one worker, and let thousands of them each handle their own i independently. You’re no longer in control of the whole process—you’re only describing what one tiny part of the system should do. This mental shift—from controlling a loop to writing instructions for an army of workers—is what makes parallel thinking hard at first.

2. Groundwork: What CUDA Assumes You Know

If you’ve spent most of your time in languages like Python, JavaScript, or even high-level C++ without touching low-level memory concepts, CUDA will feel different. That’s because CUDA code is almost always written in C or C++, and runs in an environment where you’re much closer to the hardware. Let us understand some core low level programming concepts you should know, before finally writing our first CUDA kernel in the next section.

2.1 Pointers : Variables that point to other Variable

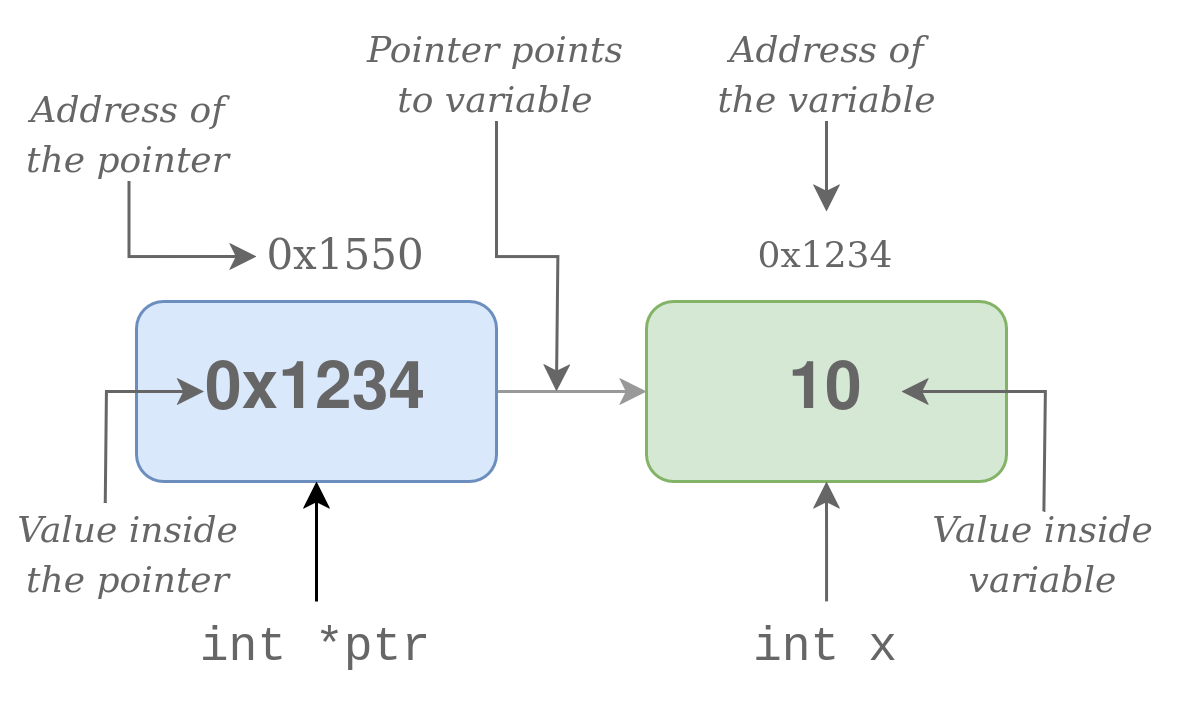

A pointer is a variable that stores the memory address of another variable. In Python, you deal with lists and objects without thinking about where they live in memory. But in CUDA (and C/C++), you often work with memory addresses directly. In this fighure below, x is an integer variable that holds the value 10, and it lives at memory address 0x1234.

The pointer ptr is declared to hold the address of an integer. When we assign it &x, we’re storing the address of x in ptr. So now ptr contains 0x1234 — it points to x.

int x = 10;

int* ptr = &x; // ptr now holds the memory address of x (e.g., 0x1234)

The pointer itself lives at a different memory location, say 0x1550. If we access *ptr, we get the value stored at the address it points to — in this case, 10. And if we use &ptr, we get the address where the pointer itself is stored — 0x1550.

2.2 Functions : Parameter Passing by Value vs. Reference

A function is a reusable block of code that performs a specific task and can take inputs (parameters) and return outputs — just like how functions work in Python. In C, when you pass by value, the function gets a copy of the data. When you pass by reference (using a pointer), the function gets access to the original, so it can modify it.

void modify(int x); // gets a copy of x

void modify(int* x); // gets the original x via address

Passing by value is like giving someone a photocopy of a document, while passing by reference is like giving them the original paper to make changes on.

2.3 Arrays and Memory Layout

In high-level languages, arrays feel like magical lists, but under the hood, an array is just a block of memory where all elements sit side by side. This figure below illustrates how array elements, like integers, are stored contiguously in memory. Each element occupies a specific block of memory, and for int types, these blocks are typically separated by 4 bytes, allowing precise calculation of each element’s address from the array’s start.

Because array elements are stored contiguously in memory, a pointer to the first element can be used to access any other element using pointer arithmetic. If ptr points to the start of the array, ptr + i moves the pointer i elements forward (not bytes — it accounts for the size of each element). For example, to increment the third element (index 2):

int arr[] = {1, 2, 3, 4};

int *ptr = arr;

ptr[2] = ptr[2] + 1; // arr[2] becomes 4

Here, ptr[2] accesses the third element of the array, just like arr[2] would. This highlights the deep connection between arrays and pointers in C.

2.4 2D Arrays and Memory Layout

In C/C++, 2D arrays are stored in row-major order — meaning all elements of the first row come first in memory, followed by the second row, and so on. So even though we access elements using two indices (row and column), in memory it’s just a flat, contiguous block. This is illustrated in the figure below.

You can calculate the memory index of any element using:

index = row * num_columns + col

In the code below, ptr[9] accesses the same memory location as matrix[2][1], because it is the 10th element in the row-major flattened memory layout (starting from index 0).

int matrix[3][4] = {

{5, 8, 9, 3},

{11, 16, 1, 6},

{6, 3, 8, 2}

};

int *ptr = &matrix[0][0];

int r = 2, c = 1;

int num_columns = 4;

int index = r * num_columns + c;

printf("%d\n", ptr[index]); // Output: 3

2.5 Stack vs Heap Memory

This is often overlooked but important. In C/C++, small, fixed-size variables (like integers or small structs) are stored on the stack — a fast, temporary memory area that automatically manages variable lifetime.

In contrast, dynamically allocated memory (such as arrays created with malloc or new) lives on the heap, which is larger but slower and must be manually managed (allocated and freed).

int x = 10; // Stored on the stack

int* arr = (int*)malloc(10 * sizeof(int)); // Allocated on the heap

We have now laid the essential groundwork of concepts—pointers, functions, memory layout, stack, and heap—on which CUDA programming is built. Understanding these basics will make your journey into parallel programming much smoother.

3. Your First CUDA Kernel: Hello World!

Now that we have a solid understanding of the foundational concepts, let’s dive into writing our very first CUDA kernel. The goal here isn’t complex computation, but to bridge the gap between CPU-style sequential thinking and GPU-style parallel execution, and to see your GPU actually do something.

A good way to learn something new, is to begin from something you already know and then connect the dots. Let us first look at a simple Hello World program in C++.

#include <iostream>

int main(){

std::cout << "Hello World!" << std::endl;

}

To execute this program on your machine, follow the following steps :

- Clone the repository that stores the code associated with my blogs :

git clone https://github.com/sanket-pixel/blog_code cd blog_code - Navigate to the directory 8_that_first_cuda_blog/1_hello_world

cd 8_that_first_cuda_blog/1_hello_world - Compile the program using the following command

g++ hello_world_cpu.cpp -o hello_world_cpu - This will create an executable

hello_worldin this directory. Execute it using./hello_world_cpu

This should print Hello World from CPU! in the terminal, as expected. Here, the g++ compiler translates your C++ code into instructions that the CPU can execute directly.

Finally, let’s write our first CUDA kernel that performs the same task — printing “Hello World” — but this time the message will come from the GPU.

#include <iostream>

#include <cuda_runtime.h> // This include statement allows us to use cuda library in our code

__global__ void gpu_hello_world(){

printf("Hello World from GPU! \n");

}

int main(){

std::cout << "Hello World from CPU!" << std::endl;

gpu_hello_world<<<1,1>>>();

cudaDeviceSynchronize();

}

To execute this program on your machine, follow the following steps :

- Navigate to the directory

8_that_first_cuda_blog/1_hello_worldcd 8_that_first_cuda_blog/1_hello_world - Compile the program using the following command

nvcc hello_world_gpu.cu -o hello_world_gpu - This will create an executable hello_world in this directory. Execute it using

./hello_world_gpu - The output should be the following

Hello World from CPU! Hello World from GPU!

Now that we have our first CUDA program running, let us dissect this CUDA program, and understand how it works from first principles.

__global__ void gpu_hello_world(){

printf("Hello World from GPU! \n");

}

The code snippet above is a function that is intended to run on the GPU.

In the GPU jargon, such a function is called kernel.

Kernel, specifically, is a special function, that can be invoked from the CPU, but runs only on the GPU. CPU, is generally referred to as host and GPU is referred to as device, since the CPU hosts the GPU in some sense. The __global__ keyword is used to specify that this function is a kernel, in that, it can be called from the host but executed on the device.

gpu_hello_world<<<1,1>>>(); is a CUDA-specific syntax. We will discuss what <<<1,1>>> means later in this blog. For now it is sufficient to understand that <<<1,1>>>, allocates 1 thread for executing this kernel.

Let us now extend our single thread CUDA Hello World, to run it with 8 threads. We would like the GPU to repeat this same Hello World from GPU operation 8 times. Just one small change in our original code will make this happen.

#include <iostream>

#include <cuda_runtime.h>

__global__ void gpu_hello_world(){

printf("Hello World from GPU! \n");

}

int main(){

std::cout << "Hello World from CPU!" << std::endl;

// HERE , we replace <<<1,1>>> with <<<1,8>>>.

gpu_hello_world<<<1,8>>>();

cudaDeviceSynchronize();

}

The output of this code, will be one Hello World from CPU! and 8 Hello World from GPU!s. The main change as explained in the comment above the kernel code is replace <<<1,1>>> with <<<1,8>>>, which essentially means launching the same kernel with 8 threads. The GPU runs 8 “print Hello World” operations in parallel.

We will understand what <<<1,8>>> exactly means in absolute detail, but at this point, it is sufficient to understand that <<<1,1>>> launches one thread and <<<1,8>>> launches 8 threads in parallel.

In summary, in this Hello World section, we first looked at how to print Hello World using the CPU, followed by the same using the GPU. The major takeaway from this section is to understand what are kernels in general, and how exactly is a kernel launched from the host, to run the same operations in parallel on the device.

Up next in Part 2: Building Blocks of Parallelism, we’ll explore the building blocks of parallelism that make CUDA powerful. From thread organization to managing memory across CPU and GPU — it’s where things start to click.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: